The Wretched Soul Will Bear the Blossoms of the Mind. The Writings of Paul Reets

- Title

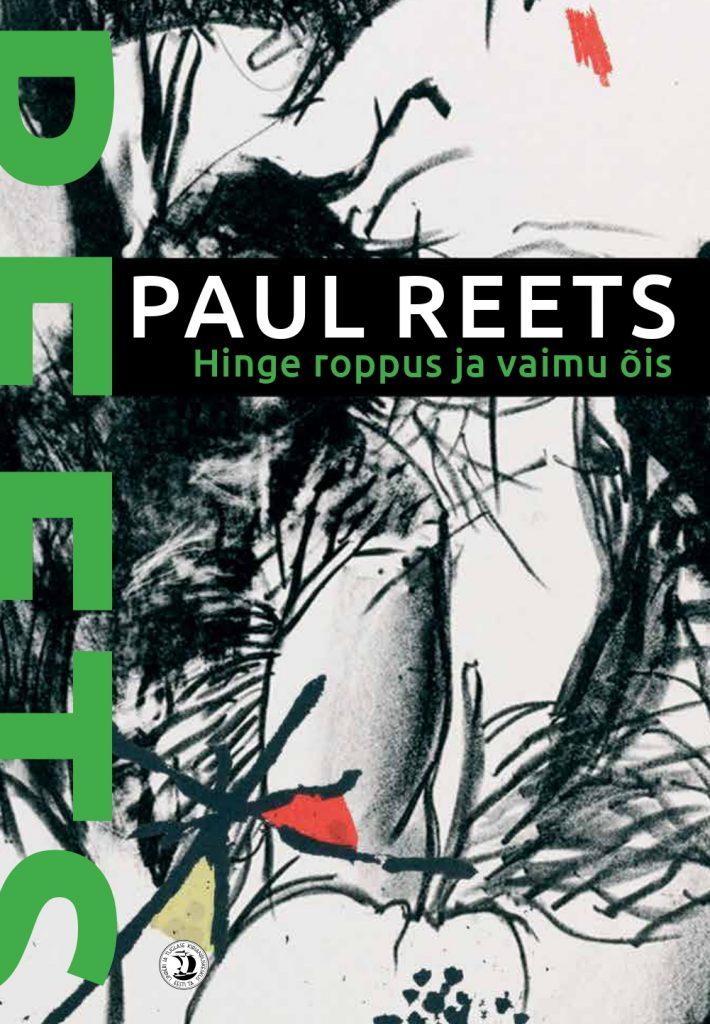

- Hinge roppus ja vaimu õis. Paul Reetsi kogutud kirjatöid

- Author

- Paul Reets

- Editor

- Jaan Undusk

- Afterwords

- Jüri Hain, Janika Kronberg ja Jaan Undusk

- Designer

- Tiiu Pirsko

- Language editor

- Brita Melts

- Publisher

- Under and Tuglas Literature Centre

- Published

- 2019

- Pages

- 672

- Language

- Estonian

Paul Reets (1924‒2016), who as a citizen of the United States called himself Paul Henri Reets, was born in Tallinn, the capital of the then independent Estonia, and finished the gymnasium of the neighbouring small town of Nõmme in 1943. Estonia was under German occupation at the time and similarly to many young Estonians of his age, Reets was conscripted into German military service. He fought against the advancing Soviet troops in Estonia in September 1944, and in Poland and Czechoslovakia in early 1945.

Estonia was occupied by the Soviets and Reets stayed in Germany as one of the approximately 35,000 ‘displaced persons’ of Estonian origin in that country. More than 800 of them attended German universities (there have never been so many Estonian students in Germany), and among them Reets, who enrolled at the University of Bonn and studied there from 1946 to 1950, mainly art history under the guidance of Professor Heinrich Lützeler. Later he described these years as the sunniest and most fruitful period in his whole life.

Yet the final destination of most of these young Estonians was the New World of great expectations. On 1 May, 1950, Paul Reets first set foot on American soil in New York and would afterwards live in Boston, the old intellectual capital of the USA. A year later, in May 1951, he was accepted into the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at Harvard University where he received his Master of Arts degree in June 1953. In May 1958, he became a citizen of the United States.

Reets never held a regular job within the field of his professional competence. For a long period, he worked part-time as a simple manager of files in the famous Lahey Clinic in Boston. The reasons for keeping a low profile were seemingly twofold. Firstly, the intellectual atmosphere at Harvard, and at other leading universities in New England and New York was overwhelmingly Jewish, which meant that Reets would have been in constant danger due to his problematic Nazi past. Secondly, an admirer of wine and women, he never aimed at marrying and having children to take full responsibility for them. His ideal was to live as a free man in a free land of spiritual pleasures. He was fond of enjoying life and art in their elementary forms, of walking, of chatting with people, drinking, gathering stones, and children’s drawings and, of course, rare books and valuable pieces of art at cheap prices. He had no material resources for systematic collecting of classical or modern art, but there were a lot of opportunities in the antique shops of Boston or New York to come upon some ancient book or picture of remarkable value. And Reets was a master of taking such chances.

During his relatively extensive leisure time, he also was a man of letters. He wrote art and literary criticism for the leading journals of Estonian diaspora culture, Mana (first published in Sweden, then in the USA) and Tulimuld (in Sweden), for other Estonian journals and newspapers in the Western world, and published some more or less academic articles on medieval Estonian sacred architecture. His translation exercises were confined to twelve Greek fragments from the work of Sappho. All these writings are gathered in this volume which is the first and, unfortunately, also posthumous book of Paul Reets. In his thirties and forties, Reets sometimes dreamed of becoming a real writer of more extensive texts, of either historical or picaresque novels. According to a family legend, he was a great-grandson of a Baltic-German nobleman, Otto Friedrich Wilhelm von Kursell. So one of his projects was to write a family saga in three parts, reaching from the old baron via his grandparents and parents down to himself. Yet being a man of Bohemian attitudes that he was, he lacked the inner patience necessary for composing long narratives. His restless literary inspiration flowed into some 500 aphorisms published in Mana in the course of approximately twenty-five years.

However, the heart of his literary talent can be found in more intimate texts, in his letters and diaries. These occasionally represent excellent examples of (almost) automatic writing with unsurpassable psychological authenticity. Paul Reets’ diaries cover the period from 1947 to 2010; the 4000 pages filled with meditations, daydreams and emotions are put down in Estonian, German and English. Amidst the broad range of subjects lies hidden a classic platonic love story. In autumn 1967, Reets spent a week of his holiday time in Toronto, mostly with the large Estonian community of this Canadian city. He fell in love at once, on the first day of his arrival, and the object of his unrequited passion was the 30-years old poetess Urve Karuks, a happily married woman and mother of two children. There was absolutely no hope for the love to be returned. The story of this passion, hitherto unpublished, is the crown jewel of the present volume.

In 2011, Reets donated his art collection consisting of about 800 items, and the better part of his library (about 800 books) to the Under and Tuglas Literature Centre of the Estonian Academy of Sciences. These are now stored in Nõmme, in the same suburban environment where Reets lived in his childhood and where he spent his schoolyears. A number of examples from his collection have been reproduced in this volume which serves as our return gift to the deceased master of reality.